Money as a Coordination Tool: Thinking About the State Like a Household

A simple “family currency” model makes the state feel less like a moral entity and more like a system: it issues tokens, sets rules, and buys predictability. That lens also reframes capitalism vs socialism, law vs gangs, and religion as compressed governance under resource constraints.

Posted by

Related reading

Military Tech Isn’t the Hard Part—War Feedback Is

China can build impressive hardware, but combat credibility comes from institutional feedback loops: reliability, integration, logistics, and honest after-action learning under real stress. The gap, where it exists, is less engineering than iteration under failure—something India has had more opport

Read Sanyal for the Lens, Not the Verdicts

Sanjeev Sanyal is most valuable as a historically grounded, institution-first way of seeing India—not as an authority to agree with wholesale. Treat his work as a corrective you interrogate, and you’ll get far more out of it than devotional certainty.

Why Israel–Palestine Feels Uniquely Intense

Many conflicts are “just” land disputes, but this one carries layered national identities, sacred geography, living trauma, and a self-reinforcing security dilemma. Global attention then magnifies every event into a proxy fight over justice, belonging, and who gets to feel safe.

The State Is a Family With Its Own Tokens (and That’s Why People Miss It)

I learned to think about “the state” the same way I learned to think about strategy games: as a system that issues resources, sets rules, and turns those rules into reality. The weird part is that once you see it like that, it becomes hard to explain to people who only experience the state as annoying laws and money as paper you work for.

I learned to think about “the state” the same way I learned to think about strategy games: as a system that issues resources, sets rules, and turns those rules into reality. The weird part is that once you see it like that, it becomes hard to explain to people who only experience the state as annoying laws and money as paper you work for.

So I started using a simple model: imagine a family that invents its own internal currency.

Call it Family Credits.

Inside the family, chores and favors get priced in Credits. Outside the family, the family still lives in a real country and trades using the national currency (rupees, dollars, whatever). The father is “the state” in the model—not because he’s morally better, but because he’s the rule-setter.

That one shift matters: the father’s “power” isn’t that he’s richer. It’s that he defines what counts as money inside the family, and he can issue those tokens.

Once you accept that, a lot of things people argue about emotionally become mechanical.

Money Isn’t Wealth. It’s a Permission System.

In the family model, Family Credits don’t create food out of thin air. The food still has to come from somewhere: either the father buys it with rupees from outside, or the family produces something to trade for rupees.

But the Credits do something else: they decide who gets to command whose time and effort.

- If a sibling wants help moving furniture, they have to bargain: “I’ll pay you 10 Credits.”

- If the father wants the furniture moved, he can just issue 10 Credits and make it happen, because everyone accepts the system he defines.

That’s the first uncomfortable point: currency is a coordination technology, and the issuer sits at the center of the coordination graph.

“Socialism” and “Capitalism” Aren’t About Working Hard

When people hear “socialism vs capitalism,” they immediately imagine a moral cartoon:

- socialism = lazy people + handouts

- capitalism = hustlers + productivity

That framing is garbage. In the family model, the difference is not “who works harder.” The difference is how decisions are made, how rewards are distributed, and where the surplus comes from.

A socialist-flavored family

In the “socialist” version, the family decides (via the father, or by consensus) what jobs need doing and assigns roles. Everyone gets guaranteed baseline access to resources, and tokens might exist but they matter less for survival.

Mechanically:

- Decision-making is more centralized.

- Roles are stickier (“you do this job, you do that job”).

- The goal is meeting needs and maintaining coordination.

This kind of system assumes coordination failure is more dangerous than incentive failure.

A capitalist-flavored family

In the “capitalist” version, family members choose what to do, trade favors using Credits, and pay some tax (a cut) back to the father. The father uses that pooled tax to fund shared needs, buy external resources, or stabilize the household.

Mechanically:

- Decision-making is more decentralized.

- Roles are fluid and demand-driven.

- Tokens become essential for comfort and often for survival.

This kind of system assumes incentive failure is more dangerous than coordination failure.

The missing axis: where the money comes from

Here’s the part most people miss: you can run either model with people working hard or barely working at all. That depends on the source of surplus.

Some families don’t rely on internal labor for the basics. They sit on something the outside world wants—oil, phosphate, strategic location, some exportable resource. In those cases, the father can sell the resource for rupees and fund a high-consumption lifestyle internally.

I think the example of Nauru is a clean illustration of the danger: when the surplus is basically “rent” from a finite resource, you can build benefits and comfort on top of it, but if the resource depletes, the entire arrangement can collapse fast. That isn’t “socialism failed” or “capitalism failed.” It’s “your surplus model evaporated.”

So if you want a useful way to describe real systems, it’s not a 1D socialism-capitalism line. It’s at least three questions:

- Who decides? (centralized vs decentralized)

- How are rewards handled? (guaranteed vs competitive)

- Where does surplus come from? (internal labor vs external rents)

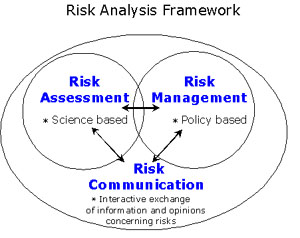

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

That’s already more honest than most political debates.

Why Laws and Justice Exist (And Why They’re Not Mainly About Being Nice)

A sovereign—whether it’s one man, an office, or a distributed system—sits at the top of the rule hierarchy. Inside its domain, there’s no higher authority by default.

That means something people hate admitting: a sovereign can technically decide what is legal and illegal, and in extreme cases it can even try to define what is right and wrong.

But the sovereign still faces a constraint: doing things through raw force is expensive.

So laws exist for a simple reason: predictability.

Predictability enables:

- long-term planning

- trade

- investment

- experimentation (“Can I build this business without getting crushed tomorrow?”)

Without predictability, every dispute becomes a personal negotiation backed by threat. Emotions rise, retaliation spirals, and you end up living in permanent conflict mode.

Justice systems, even flawed ones, often beat “no justice system” for the same reason: they prevent private revenge from escalating into constant violence. Justice monopolizes retaliation and turns it into procedure.

The State vs a Gang: Same Muscle, Different Time Horizon

At street level, a gang and a state can look identical:

- both use force

- both extract resources (taxes, protection money)

- both enforce rules

The difference isn’t “the state is good and gangs are evil.” That’s a bedtime story.

The real difference is time horizon.

- A gang optimizes for extraction.

- A state (if it wants to survive) optimizes for continuity.

And here’s the twist: once a gang wants steady revenue, it starts acting more like a government. It becomes “honorable,” not because it found God, but because fairness reduces resistance and lowers enforcement costs. Dispute resolution appears. Consistency appears. People start paying more willingly because the alternative is worse.

That’s also why excluded communities often build informal systems when the formal state doesn’t recognize them. If you can’t access the official courts and protections, you’ll use whoever can enforce outcomes—legal or not. Justice fills vacuums. Always.

Religion Was a Proto-Constitution (Because Law Is Expensive)

Modern, codified law is not “the default human condition.” It’s a luxury that requires a lot of infrastructure:

- literacy

- record-keeping

- precise language

- bureaucracy

- institutional continuity

Before that stack existed, societies still needed order. Religion solved the same underlying problem at lower cost.

Not primarily “why lightning happens.” That explanation is too shallow.

Religion works as compressed governance:

- rules people can memorize

- legitimacy for those rules

- enforcement outsourced to something you can’t bribe, outrun, or appeal to

That’s why religions functioned like proto-constitutions: they reduced variance in behavior, created predictable social expectations, and let large groups cooperate without needing a police officer on every corner.

Even “good vs bad” makes more sense in this frame. In fragile societies, “good” often meant “predictable,” and “bad” meant “destabilizing.”

Why Some Religions Are Syncretic and Others Become Dogmatic

I don’t think it’s an accident that resource conditions shape religious structure. When survival is stable and surplus exists, societies can afford ambiguity and pluralism. You get syncretic, absorbent frameworks—religions that can layer philosophies and tolerate variance.

When survival is volatile and resources are scarce, deviation has a higher cost. Cohesion matters more. You get tighter boundaries and stricter enforcement.

This doesn’t make one “enlightened” and the other “backward.” It means they solved different coordination problems under different constraints.

Even moral rules can map onto survival economics:

- norms that emphasize reproduction when population replacement matters

- norms that restrict wasteful consumption when food or inputs are scarce

- norms that prioritize conformity when trust is fragile

That’s not cynicism. That’s systems thinking.

Feudalism → Bureaucracy → Democracy: Governance Evolves Under Pressure

Feudalism is what happens when insecurity is chronic. If you don’t know who’s coming to kill you and take your stuff, protection becomes the most valuable product in the market.

A protector doesn’t need to be a superhero—just stronger than you, and willing to fight. Add a few loyal supporters and you get a local lord. Stack lords into hierarchies and you end up with counts, dukes, kings, emperors: defense scaling through loyalty.

But once populations concentrate and agriculture becomes predictable, loyalty doesn’t scale. A ruler can’t personally manage a massive population. Procedure replaces personal ties. Bureaucracy becomes unavoidable.

Then bureaucracy produces its own failure mode: distance between power and consequence. Corruption appears not as a glitch, but as a structural temptation.

That’s where legitimacy becomes central. When coercion is too expensive, consent becomes cheaper. Democracy shows up less like a moral awakening and more like a stability technology: it converts rebellion into process, resentment into delay, obedience into participation.

Don’t Take the Current World for Granted

Modern geopolitics and “normal life” sit on a ridiculous stack of dependencies: stable populations, abundant energy, specialists who know how the machine works, institutional memory, supply chains, gatekeepers, infrastructure, and a general expectation that tomorrow will resemble today.

That web is both strength and fragility. If enough of those conditions stop holding, society doesn’t heroically “innovate upward” by default—it often simplifies into older, tougher forms: local strongmen, loyalty networks, force-backed order. History doesn’t only move forward; it also reverts when constraints return.

The scariest part isn’t a single weak point. It’s the assumption that because the system has held, it will automatically keep holding.