The Justice Speed Trap

Court reform isn’t a simple race from slow to fast. If you accelerate decisions without preserving accuracy and predictability, you trade friction for fear—and society adapts in darker, more corrosive ways.

Posted by

Related reading

India and the US: Asymmetric Interdependence

India isn’t existentially dependent on the US, but it is tightly entangled with America across export earnings, the tech stack, capital flows, and Indo-Pacific security. The relationship is best understood as interdependence with asymmetry—India can disagree, but US shocks transmit quickly and uneve

India’s Courts Don’t Need Toughness. They Need Speed.

India hasn’t built a justice system for everyday disputes—it has built one that prioritizes idealized accuracy while rationing justice through delay. When resolution takes decades, procedure becomes punishment and legitimacy drains away.

After the Blasts: How a US–Russia Nuclear War Breaks the Systems India Depends On

A US–Russia nuclear exchange wouldn’t be a bigger version of conventional war—it would fracture climate, agriculture, and global trade for years. India might not be directly targeted, but monsoon disruption, food stress, energy shocks, and supply-chain collapse would still hit hard.

The Justice Speed Trap: Why “Fixing” Courts Can Make a Country Worse

There’s a popular story people tell about broken judiciaries: things are slow, therefore the economy is slow; fix the courts and growth will unlock.

It’s a satisfying narrative because it’s linear. And it’s wrong in the way most linear narratives are wrong: it takes a real constraint and turns it into a single-point cause.

A slow judiciary absolutely distorts society. It changes how people build companies, how they write contracts, how they settle disputes, how much they delegate, and what risks they’re willing to take. But the more interesting (and more dangerous) idea is this:

If you “fix” slowness by flipping the system into speed-first justice—without holding accuracy and predictability constant—you don’t get efficiency. You get fear.

And fear doesn’t just change what people do. It changes who people become.

This is the justice speed trap: the tail risks on both sides are catastrophic. There’s a narrow sweet spot in the middle. Miss it, and society adapts in ways that are rational individually and ugly collectively.

Justice has two failure modes, not one

A judiciary can fail in at least two broad ways:

- Too slow: decisions arrive after life has moved on. Justice exists as an abstract ideal but not as a usable service.

- Too fast and unreliable: decisions arrive quickly, but the system is sloppy, pressured, politicized, or trigger-happy. Justice becomes a high-speed machine that sometimes crushes the wrong person.

Most people can feel the pain of slow justice: years of waiting, legal costs, endless adjournments, uncertainty. But the pain of fast, inaccurate justice is different. It’s not just frustration. It’s existential insecurity.

Slow systems create friction. Fast-wrong systems create terror.

And the distinction matters because societies respond differently to friction than they do to terror.

The core mechanic: power weaponizes whatever the system normalizes

Here’s the simplest model that explains why both tails are dangerous:

Power weaponizes the dominant constraint.

- When slowness is normal, power learns to use delay as leverage.

- When speed is normal, power learns to use timing as leverage.

Same predator. Different habitat.

When slowness is normalized, delay becomes a weapon

In slow systems, “winning” often looks like outlasting the other side:

- drag proceedings until the weaker party runs out of money

- multiply hearings and procedural complexity

- convert time into a tax that only the poor actually pay

The strongest actors don’t need the truth to win. They just need endurance. Justice becomes attrition warfare with paperwork.

When speed is normalized, timing becomes a weapon

In fast systems, “winning” often looks like not giving the other side time to react:

- rush hearings before evidence can be gathered

- rely on confessions or shortcuts instead of deep investigation

- use pre-trial constraints as punishment without calling it punishment

- pressure defendants into quick closure because the process itself is the threat

The strongest actors don’t need endurance. They need control of the clock. Justice becomes procedural ambush.

Slow justice changes society by pushing people into informality

Let’s talk about the behavioral outcomes—the “outside the courtroom” effects—because that’s where the real costs show up.

A slow judiciary teaches a population some basic lessons:

1) Don’t escalate disputes formally unless you have to

If formal resolution is slow, expensive, and uncertain, people route around it:

- disputes get settled through networks

- contracts become relational (“I trust you”) instead of enforceable (“I can sue you”)

- reputation and personal ties substitute for legal clarity

This isn’t romantic. It’s not “community.” It’s a workaround culture.

2) Stay small, stay controlled

If disputes take forever, delegation becomes dangerous. The more you scale, the more surface area you expose to legal risk.

So organizations adapt:

- founder control stays tight

- family ownership becomes attractive

- hiring outsiders feels like importing uncertainty

- paper trails become something you minimize, not something you invest in

It’s not that people don’t want to build large institutions. It’s that large institutions are brittle when enforcement is slow and unpredictable.

3) Risk appetite collapses asymmetrically

Slow systems create a specific kind of downside: unbounded time risk.

One dispute can freeze assets, attention, and growth for years. That changes what “risk” means:

- you choose projects with quick paybacks

- you avoid anything that can get stuck in limbo

- you prefer cash flow over scale

- you treat formal compliance as a cost center, not an enabling layer

This produces a society that can be entrepreneurial and scrappy, but structurally allergic to clean scaling.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

The mood isn’t fear. It’s exhaustion and cynicism. People complain loudly. They still live.

Fast-but-inaccurate justice changes society by pushing people into invisibility

Now flip the distortion.

A fast judiciary that is unreliable doesn’t just create bad outcomes in court. It changes the entire social operating system because it teaches a darker lesson:

Visibility is risk.

1) People learn to stay off the radar

In a speed-first system with weak accuracy safeguards, the rational strategy becomes:

- don’t stand out

- don’t attract attention

- don’t be the “example” someone needs to make

This shows up as:

- self-censorship

- avoidance of activism or public conflict

- preference for conformity over originality

The most damaging part isn’t the wrong decisions. It’s the behavioral shadow those wrong decisions cast over everyone else.

2) Organizations centralize and micromanage

Slow justice punishes delegation through friction. Fast-wrong justice punishes delegation through liability.

If the system can move quickly against you, then every subordinate becomes a potential threat vector:

- fewer empowered employees

- decisions pulled upward

- paranoia disguised as “strong leadership”

- obsession with control, not outcomes

This can look efficient from a distance—tight command structures, quick decisions—but it’s fear-driven centralization. It scales poorly and collapses under stress.

3) Innovation becomes hidden, approved, or dead

In a fast-unreliable environment, innovation doesn’t disappear—it changes form:

- it goes underground

- it stays small

- it becomes incremental and “safe”

- it clusters around whatever is politically or institutionally protected

You end up with apparent order and hidden stagnation. The place can look stable right up until the human capital quietly leaves or mentally checks out.

4) Compliance replaces trust

This is the psychological shift that matters:

In functional systems, people ask: “Is this legal?”

In speed-wrong systems, people ask: “Will this attract attention?”

When law becomes a threat surface rather than a coordination mechanism, society becomes cautious in the worst way: not thoughtful, just scared.

Which failure mode is “better” for a country?

If you force a choice, slow justice tends to produce stagnation. Fast-but-inaccurate justice tends to produce decay.

Stagnation is awful. Decay is worse.

Why?

Because stagnation preserves the social fabric while distorting behavior. People route around the state. They build parallel systems. They adapt. It’s inefficient, but it’s survivable.

Fast-wrong systems hollow out initiative itself. They don’t merely distort growth—they distort the human traits growth depends on: trust, experimentation, dissent, delegation, ambition.

Slow systems make people tired. Fast-wrong systems make people afraid. Tired societies still argue, build, and muddle through. Afraid societies shut down.

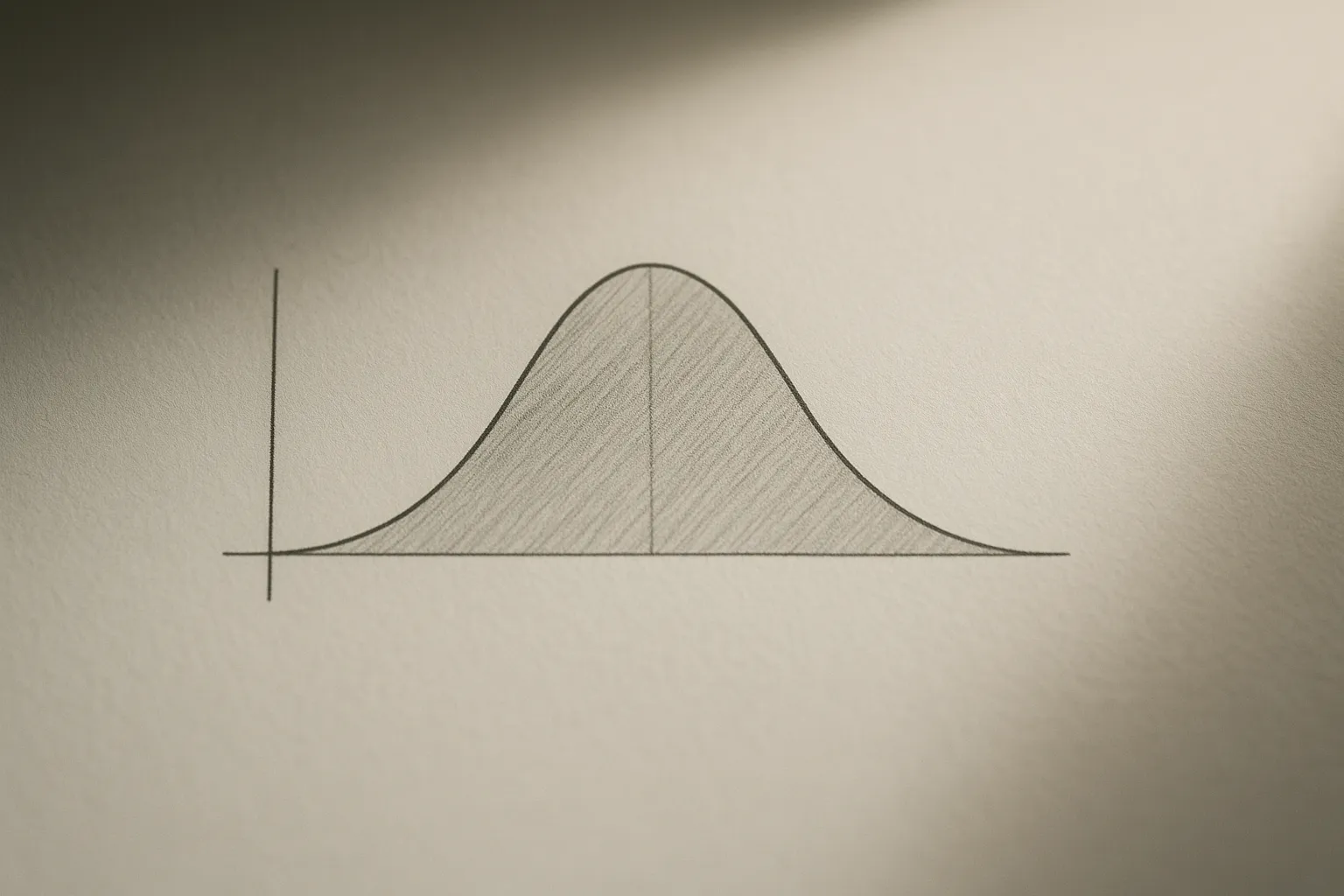

The bell curve: there’s a sweet spot, and it’s narrow

So yes: blaming a slow judiciary as the cause of economic bottlenecks is too harsh. It’s more accurate to say the judiciary is a constraint that shapes what kinds of growth are rational.

And here’s the uncomfortable part: you can’t fix that constraint by swinging hard in the other direction.

Justice sits on a bell curve:

- Too slow → justice denied through attrition

- Too fast → justice denied through error and intimidation

- Middle band → justice is predictable enough to delegate and fast enough to matter

The middle band isn’t perfection. It’s not “always correct.” It’s “boringly predictable” with errors that are detectable and correctable without destroying lives.

That’s also why simplistic reform slogans are dangerous:

- “Speed up courts” can become a machine for rushed outcomes.

- “Maximize due process” can become a machine for endless delay.

The sweet spot requires discipline, not ideology. It requires a system that makes errors expensive enough to avoid—but cheap enough to admit and correct.

The real design target isn’t speed. It’s error control.

A judiciary doesn’t become healthy by worshiping slowness or speed. It becomes healthy when:

- truth remains the objective, not closure

- no single actor controls the clock and the narrative

- correction mechanisms work fast enough to matter

- outcomes are predictable enough that society can safely delegate

If those conditions aren’t met and sustained, the system will drift into one of the tails. And once a society adapts to a tail, the adaptation becomes self-reinforcing.

Conclusion

A slow judiciary pushes society into informality, tight control, and cautious scaling—bad, but often resilient. A fast but inaccurate judiciary pushes society into invisibility, centralization, and fear—efficient on paper, corrosive in reality. The real goal isn’t “fast” or “perfect,” it’s staying inside a narrow band where justice is predictable and correctable. Miss that band for long enough and, yes, things don’t just underperform—they rot.