Why Your First Customers Shouldn’t Be Friends and Family in India

In many Indian social circles, selling inward turns your offer into a referendum on your identity—warping pricing, authority, and confidence. Build legitimacy with strangers first, then let proof travel back into your network.

Posted by

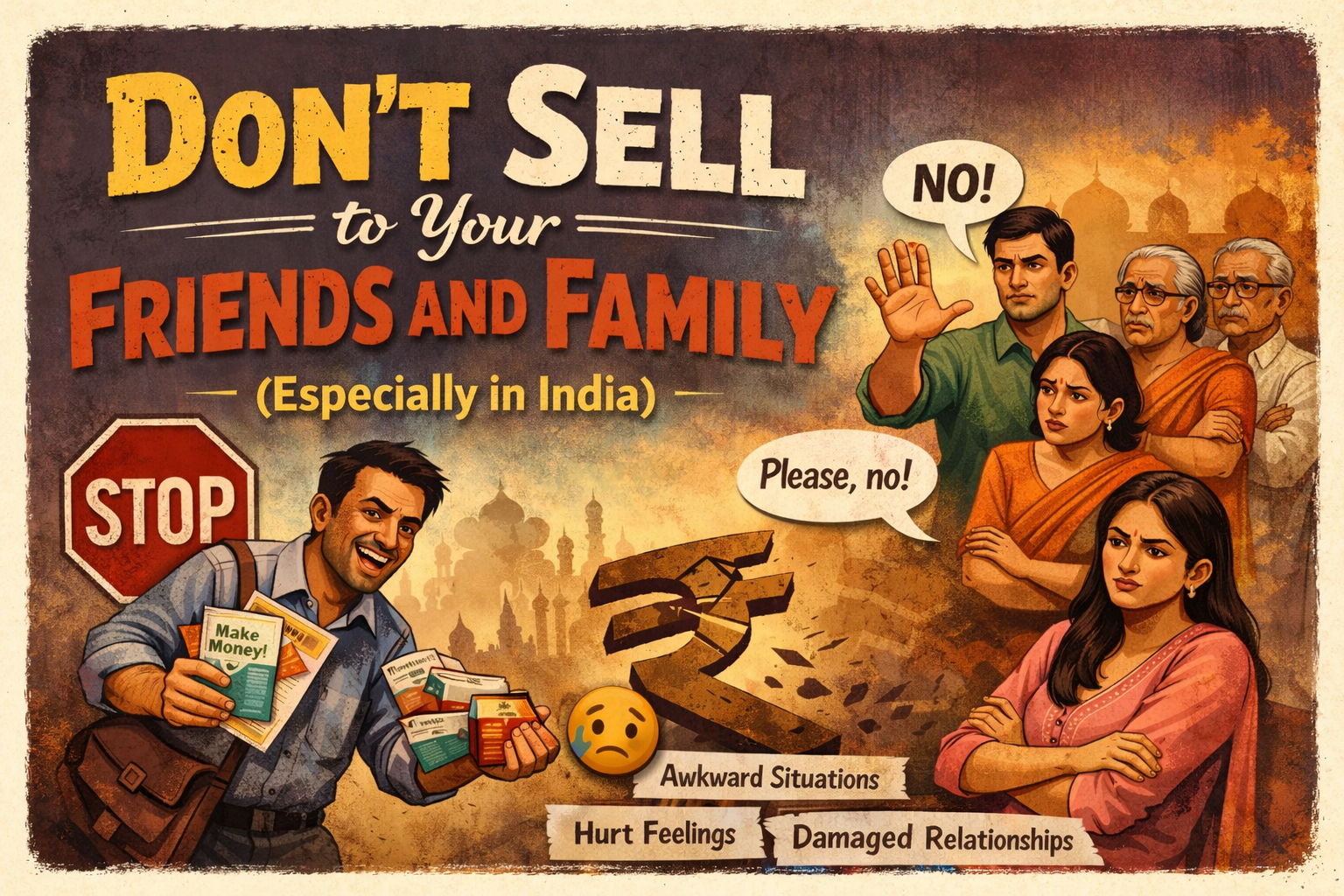

Don’t Sell to Your Friends and Family (Especially in India)

If you’re starting a business in India and your first instinct is to “announce it” to friends and family, you’re probably about to waste weeks of momentum and take a few unnecessary hits to your confidence.

If you’re starting a business in India and your first instinct is to “announce it” to friends and family, you’re probably about to waste weeks of momentum and take a few unnecessary hits to your confidence.

This isn’t because Indian friends and family are uniquely bad people. It’s because the social physics are different. In most circles here, your identity doesn’t sit next to your product—it swallows it.

The moment you try to sell something inward, people don’t evaluate the offering. They evaluate you. And that contaminates everything: pricing, authority, trust, even basic willingness to engage.

The real problem: identity precedes utility

When strangers see a service, they ask:

- Is this useful?

- Is it trustworthy?

- Is it worth paying for?

When friends and family see the same thing, they ask something else:

- Why is he doing this?

- Since when is she an “expert”?

- Why should I pay you for it?

Even when the product is legitimately good, it gets reframed as:

- “His little thing”

- “Her experiment”

- “Just a phase”

That shift is deadly. Because it drags your work out of the market and into the relationship.

And relationships in India come with a lot of baggage: status, hierarchy, obligation, guilt, “log kya kahenge,” and the unspoken agreement that nobody should suddenly outgrow the version of themselves everyone is comfortable with.

The “friends and family discount” is not generosity

Everyone has heard this line: “Friends and family discount?” In many Indian contexts, that discount isn’t about saving money. It’s about preserving hierarchy.

Paying full price implies a few uncomfortable things:

- You’re a professional now, not a kid trying something

- Your time has market value

- The relationship is now peer-to-peer, not senior-junior

- You’re allowed to set terms

So the discount becomes a social tool: I’ll support you, but I’m not going to validate you fully.

If you refuse the discount, you’re suddenly “changed.” You’ve “become too money-minded.” You’re “taking advantage.” And if you accept it, you’ve trained them to treat your work like it doesn’t deserve real pricing.

Either way, you lose.

Services are the worst thing to sell inward

Products have some buffer. A physical product can be evaluated without directly challenging the relationship. Even then, people will bargain and lowball—but at least there’s a thing.

Services are more personal and more fragile.

With services, you are the product:

- your judgment

- your taste

- your time

- your authority

And authority is exactly what familiarity destroys.

People who have known you since school, who have seen you in pyjamas, who have argued with you at family functions, do not easily switch into “client mode.” They don’t want to. It feels weird. It asks them to update their mental model of you. Most people resist that update.

That’s why service professionals often have an unspoken rule: don’t treat family, don’t consult for friends, don’t mix it. It’s not arrogance—it’s self-preservation.

If you’ve ever wondered why so many people happily pay for a service outside but want it free inside, this is the reason. Inside the relationship, money becomes moral.

Why personal branding feels taboo (and sometimes gets punished)

There’s also a separate, uncomfortable layer: personal branding.

In many Indian social environments, publicly asserting your work—posting about it, talking about it, “building in public”—doesn’t read as marketing. It reads as self-importance.

Not always, not everywhere, but often enough that you should factor it in.

Visibility can trigger norm enforcement:

- “Why is he acting big?”

- “Who is she trying to impress?”

- “Show-off”

- “So much attitude now”

This isn’t always pure envy. Sometimes it’s a communal instinct to keep everyone at the same level. If someone becomes too visible without externally validated status (big title, big company, big institution), it creates discomfort.

So you get this weird Indian paradox:

- If you’re small and you speak loudly, you’re “overconfident.”

- If you become big first, then speaking loudly becomes “inspiring.”

Respect follows scale, not effort. That’s not a motivational quote. It’s just how social proof works here.

Friends and family aren’t neutral—they often reduce your perceived value

The worst part isn’t that friends and family don’t buy.

It’s that they can actively lower the perceived seriousness of what you’re doing.

When your circle treats your business like a hobby, you start performing for them:

- over-explaining

- justifying your pricing

- seeking validation

- changing the offer to sound “reasonable”

- discounting to avoid conflict

That’s not marketing. That’s slow erosion.

And if you’re not careful, it changes your own self-perception. You start thinking, Maybe I’m not worth paying. You start negotiating against yourself.

Meanwhile, a stranger would have just asked: “How much?”

The only safe role for friends and family: moral support

This needs to be said bluntly: friends and family are not your distribution channel.

They are useful for:

- emotional encouragement

- celebrating milestones

- giving you a place to be human

- reminding you that your life is bigger than your startup

They are not reliably useful for:

- early revenue

- referrals

- unbiased feedback

- market validation

- serious adoption

When you force them into those roles, resentment builds on both sides. You feel unsupported; they feel pressured. Then you get the worst outcome: you lose time and you damage relationships.

Distance creates legitimacy

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: distance sells.

When your product is mediated by something external—an agency, a platform, a formal process, even a neutral website—it becomes easier for people to pay.

Not because the service changed, but because the relationship changed.

A third-party wrapper creates a psychological firewall:

- “This is a real service, not my friend’s request.”

- “This has a system.”

- “This is how it’s priced.”

- “Others pay for it.”

Institutions, even small ones, reduce moral negotiation. They take your work out of the emotional space and put it into the economic space.

That’s why, practically, the “Indian founder playbook” often looks like this:

- Sell to strangers first

- Build proof outside your circle

- Let outsiders validate it through money

- Let that validation travel backward into your circle

It sounds cold, but it’s actually kinder. It preserves relationships and protects your pricing.

What to do instead (if you want to stay sane)

If you’re building something serious in India, a few rules will save you months:

- Don’t pitch your product to friends and family as your primary plan.

- Don’t use them as the benchmark for whether your idea is “good.”

- Don’t beg for referrals from your circle early on.

- Don’t price your service based on what feels socially comfortable.

Instead:

- sell to people who don’t know you

- create a professional wrapper (process, landing page, clear offer)

- let paying users teach you what the market wants

- keep a clean boundary between relationship and revenue

Ironically, once strangers pay you, your circle often becomes supportive later. Pride arrives after proof. That’s just how it works.

Conclusion

In India, friends and family usually aren’t your early adopters—they’re your early resistors. Trying to sell inward turns pricing into morality, business into identity, and marketing into social negotiation. Build your legitimacy outside first, through strangers who can evaluate you without baggage. Then let success do the talking.